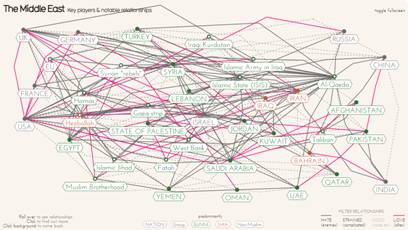

| TIME TO REDRAW THE MAP OF THE MIDDLE EAST, 27 September 2013

editorial Steven Blockmans, senior research fellow, head of EU Foreign Policy CEPS

As the blood-soaked stalemate in Syria drags on,

territorial divisions in the country are becoming

more entrenched. Bashar al-Assad’s regime

is tightening its grip on the western, most populous

part of the country and rebel forces are consolidating

their hold on the Euphrates valley.

As al-Qaeda-linked groups mete out sharia law

in their caliphates in the eastern desert areas of

Syria, Kurdish groups are creating an autonomous

region in the north-east of the country. As feared, Syria’s civil war is spreading to its neighbours, the

most vulnerable of which is lebanon. A weak state of five million

people, lebanon has already taken in more than 700,000 syrian

refugees across its porous borders, most of them Sunnis. Vicious

attacks across the Sunni-Shia divide are on the increase.

The long border between the eastern deserts of Syria and the

western deserts of Iraq is also losing its physical reality as al-

Qaeda fighters move freely back and forth. the fact is the syrian

civil war has reignited a sectarian conflict that has never

really died down since the US invasion of Iraq in 2003. In all three states, the power of central government is waning as ethnic

and religious groups retreat to their own well-defended and near-autonomous

enclaves. The heart of the Middle East now consists of porous,

fragmented countries stretching from the Mediterranean to I.R. of Iran. The external borders of this bloc are not inviolable either. Syrian mortars

have landed in the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights, and the violence

in Syria has frequently spilled over the border with Turkey, across

which insurgent groups advance and retreat at will. Turkey has so far

taken in 460,000 syrian refugees; Jordan more than half a million. All this heralds the end of ‘Sykes-Picot’, the infamous 1916 agreement

in which Britain and France dealt with the ‘Syria Question’. This agreement

formed the basis for a treaty negotiated during and after the 1919

Versailles Peace Conference to carve up the Ottoman territories in and

old-style imperialist land grab. France and Britain drew lines to divide

their zones of influence in Mesopotamia and Palestine, without

heeding the ethno-religious and geographical realities on the ground. Fear of instability in the Middle East is pushing the US, Russia, the EU and its member states to talk of a diplomatic solution

to the syrian conflict. But a hard-and-fast agreement is unimaginable

if world powers stick to Sykes-Picot and ignore the wider

conflicts playing out in syria: a regional struggle between shia and

sunni that is also a longstanding conflict between iranian-led

Hezbollah and iran’s traditional enemies, notably saudi Arabia;

territorial disputes between Israel and its Arab neighbours;

and the independence drives of the Palestinians and the Kurds.

Sykes-Picot is dead and should be buried. It stands in the way of creating

a durable peace in the Middle East. Any way out of the quagmire

will require a grand bargain - one that establishes a new order in the

whole region and draws borders accordingly. See longer CEPS Commentary by Steven Blockmans (forthcoming):“Vanishing lines in the sand – why a new map of the Middle East is necessary”.

__________________________________________________________________

So Much for the Arab Spring, Ayaan Hirsi Ali, Posted: 08/19/2013 10:39 am. Huffington Post So much for the Arab Spring. In Cairo, Egyptian history appears to have completed a bloody full circle. First the crowds filled Tahrir Square to demand the end of a military-backed dictatorship. Then, just two years later, the crowds filled Tahrir Square again to demand the restoration of a military-backed dictatorship. Now, within weeks of the coup that overthrew the democratically elected government of Mohamed Morsi, massacre has become the new normal in Cairo. In 2011, Egypt seemed to have reached a turning point -- but it ended up turning 360 degrees. We are back to a "temporary" martial law that will probably last for years.

However, in the Middle East as a whole -- and probably in Egypt, too -- the revolutionary story is far from over. In Syria, a civil war rages that is increasingly sectarian in character. In Tunisia, protests against the Islamist government are growing in the wake of yet another assassination of a secularist politician. In Libya, violence between rival militias is on the increase. There, as well as in Iraq, we are seeing car bombs and mass jailbreaks.Jihadist violence is spreading like an epidemic as far afield as Mali and Niger. Yemen has become so dangerous that two weeks ago Britain and the United States had to evacuate their embassies in the capital, Sana'a.

Only in the wealthy monarchies of the Gulf does an uneasy stability persist. But it depends heavily on the high price of oil, which allows the various royal dynasties to bribe their peoples into docility. Less wealthy monarchs, such as the king of Jordan, fear for their thrones. The Arab Spring was supposed to usher in a more democratic political order in the Middle East. In the United States, conservatives and liberals alike rejoiced in early 2011 at the prospect of a new Egypt run by cool young Google executives. This was to be a Twitter-feed revolution.

Instead, the immediate beneficiaries were bearded Islamists committed to the imposition of Sharia. One Islamist faction -- the Muslim Brotherhood -- may have bungled its chance to rule in Egypt. But others are still riding high.

The chance for an effective Western intervention to help topple the Syrian dictator has been more or less blown precisely because extreme jihadist groups have taken over the war against President Bashar al-Assad. Osama bin Laden may be dead, but al-Qaeda is very much alive. It was the interception of a secret message between Ayman al-Zawahiri, its chief, and Nasser al-Wuhayshi, leader of the Yemen-based al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, that earlier this month prompted America to shut down 19 diplomatic posts throughout the region -- a humiliating illustration of weakness by the superpower that once dominated the Middle East. |

What has gone wrong?

-

The protests that were misleadingly labeled "the Arab Spring" exposed multiple conflicts between different and sometimes overlapping groups. At first it was conflicts around economic issues and political freedoms that came to the fore. Youth unemployment, high food prices and rampant corruption: these were the grievances that led to the overthrow of the despots in Tunisia, Egypt and Libya. They still matter. In Cairo, many of the same arguments were used against Morsi as had previously been used against Hosni Mubarak. But we now see just how complex and intricately layered these young societies are. For three other forms of conflict are now clearly visible.

The first revolves around identity: Who are we and how do we organize our society? Here the cleavage is between those who would emphasize an Arab national identity and those who see an Islamic religious identity as more important. This division dates back to the fall of the Ottoman Empire.

Note that even within these groups there are subdivisions. Some pan-Arabists are liberals, others are socialists, and still others are unabashed militarists. Some are in favor of the strict separation of church and state; others would allow religious leaders and institutions some control. The pan-Islamists are united in their endeavor to apply Sharia, but disagree about how soon and how literally that should be done.

The second divide is urban versus rural. People in the region's cities tend to be less religious and more Western-oriented. The country dwellers are more conservative and deeply suspicious of the West. This picture is further complicated by those trapped in a no man's land between the rural and urban areas, in the sprawling shantytowns where millions live in squalor with little prospect of employment, reliant on government-subsidized fuel and bread.

-

The third cleavage that predates these new troubles is sectarianism, above all the region-wide rivalry between the Sunni and Shi'ite brands of Islam.

Given the breadth and depth of these fissures that run through Middle Eastern society, it is tempting to conclude that democracy is bound to fail there. Sooner or later, the pessimists now argue, the countries of the Arab Spring will revert to the old kind of harsh rule by "strongmen."

To remain in power in these shame-and-honor cultures, as David Pryce-Jones described more than 20 years ago in "The Closed Circle," it seems a leader has to combine most if not all of the following strategies: generating an aura of fear, ruthlessly eliminating rivals, appointing trusted friends to run the army and security services, using foreign alliances to his advantage and -- of course -- placing busts, portraits and statues of himself in every public space. Some observers are already wondering how long it will be before the de facto ruler of Egypt, General Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, ticks all of these boxes. Yet I am not quite so pessimistic as to expect a complete restoration of the old order. The Arab Spring may appear to have failed, but in many important respects the Arab world has been changed irrevocably.

-

First, the institution of tribalism is not as strong and cohesive as it used to be. Individuals within a tribe or clan have developed other loyalties and can defy traditional forms of authority in ways that were unthinkable a generation ago. The combined factors of urbanization, young demographics, displaced peoples and emigration will further erode tribal and clan loyalties

Second, the appeal of radical Islam is beginning to wane. This trend is paradoxical because Islamists continue to enjoy considerable grassroots loyalty. However, after what people have experienced in countries where Islamists have come to power -- notably in Ayatollah Khomeini's Iran and the Taliban's Afghanistan -- it is no longer self-evident that Sharia is the answer to all the problems of modernity. This is the key to the backlash against the Islamists that we have seen in Egypt, Tunisia and elsewhere. Islamists thrive in opposition and in chaos but fail miserably in government.

Third, the effects of globalization have changed attitudes towards the West. Thanks to migration and telecommunications, Arabs in particular and Muslims in general are now physically and virtually connected to Europe and the United States as never before. They may not approve of everything they see in the West, but they nevertheless are seeing how Western political institutions of freedom actually work.

-

Fourth, the emergence of hitherto oppressed interest groups cannot be reversed. Women, religious minorities and even homosexuals remain highly vulnerable in the Middle East and North Africa. But such groups are gaining strength through organization. If you are a woman who has been raped, you are better off going to a women's group than to your local despot. Feminism, in particular, has been one of the surprise winners of the past three years in Egypt.

- Finally, the attitudes of Americans and Europeans have changed. In the past, any despot in the region worth his salt understood how to present himself as strategically vital to Western interests. For better or for worse, that game is now almost over. Rulers who cannot credibly claim to have popular legitimacy can no longer count on being propped up by Washington, London or Paris.

|

Significantly, the restored military regime in Egypt is counting on the Gulf states, not the United States, to bankroll it. Last Thursday, President Obama interrupted his holiday to give a speech canceling joint U.S.-Egyptian military maneuvers. The minority of Americans who still care about the Arab Spring are urging him to go further. But even if he cuts U.S. aid to Egypt, it won't make much difference. The Saudis and Emiratis can more than compensate.

Do all these profound changes mean the Middle East is on the brink of a glorious new era of peace, democracy, freedom and prosperity?

On the contrary. The collision between the region's traditional divisions and these new and disruptive trends will be anything but peaceful. I look ahead with trepidation and pity towards a prolonged period of conflict as revolutionary and religious wars coincide and interact. All we can say with any certainty is that there can be no return to the old days.

This was indeed a turning point -- even if the Arab world has turned in a direction that few Western commentators expected two years ago.

____________________________________________________________________

January 2013, CEPS drafted a commentary on The EU’s External Action towards

the Middle East: Resolution required, in which is addressed that one can foresee certain foreign policy challenges that the EU will have to address

this year. Cultivating workable ties with Ukraine, Russia and other neighbours in the east,

reviving the transatlantic partnership in trade, rebalancing alliances with Asian countries,

and pooling and sharing defence capabilities will all command the attention of those who

shape the EU’s external action. But the number one challenge that will take up most of the

Foreign Affairs Council’s time is the Middle East.

Contributions have also to come up with the Middle East peace

process where, to render the problem even more complex,

it is not only the usual suspects, but also new actors such

as Turkey, Brazil, and Qatar that want to have a say.

So to remain relevant the European Union will have to

invent new instruments and new tools, and draft a new

narrative of what it is about. indeed, the extent to which

Europe has lost confidence is “striking”, and Vimont

believes that “we have to change the mood”.

Europe seems

to have forgotten its extraordinary past performance,

and the numerous international agreements that it has

been able to conclude in the last 20 years, and become

an inward-looking continent full of fear and concern.

Thus, by putting its house in order

through the establishment of a new

administration, the EU will also

provide a message of hope.

Third countries have been waiting

decades for this to happen. Vis-à-vis

these countries, the fundamental

step for the EU will be to establish

a constructive dialogue based on

openness and the ability to listen.

Until recently Europe had taken

a somewhat patronising attitude

towards third countries, with partners

feeling as if they were being “pushed in a certain

direction”. Now the aim will be to give rise to a “true

and genuine partnership”, including with countries like

Tunisia and Egypt, which are “looking for dignity”. This

will be a formidable task.

Countries of the Arab Spring are in crisis; violence of ultraconservative Muslims, growing economic problems, authority vacuum.

Is democratic reform actually possible? The short answer is no. 2011 should be seen as 1848, as the moment when the people first initiate the fall of the repressive state. It can take decades till institutions are established, on which a viable democratic system can be built.

But currently, the events of the driving force, which is a dangerous situation.

Ideologies are depleted. The on modernize liberalism of the 30's and 40 failed, Arab nationalism failed. Of the fundamentalism is life artificially prolonged by the war against the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and the Iranian revolution, that is to say by the glow of something else that was promising. But now, it is really discredited.

A more likely scenario if things are not reversed in the good directions, is a series of failed states and social and an economic morass that the region will change into a source of misery.

Syria is no longer Syria. Think of warlords and the death of the urban Syria. There is concern about the impact of the war in the region.

The three countries in North Africa are in a fragile stage in their development. But in all these three states failure is not yet a settled matter. There is still a chance to lift out of the morass and draw the right course of action.

One change is that people take to the streets if something does not please. The region has entered a new era, as in 1848.

|