|

RUSSIAN FEDERATION |

| __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ |

| Russia, also officially known as the Russian Federation, is a state in northern Eurasia. It is a federal semi-presidential republic, comprising 83 federal subjects. At 17,075,400 square

kilometres (6,592,800 sq mi), Russia is the largest country in the world.

Russia is also the ninth most populous nation with 142 million people. It extends across the whole of northern Asia

and 40% of Europe, spanning 9 time zones and incorporating a wide range of environments and landforms. Russia has the world's largest reserves of mineral and energy resources. It has the world's largest forest reserves and its lakes contain approximately one-quarter of the world's fresh water. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| At a meeting with NATO Secretary-General Jaap de Hoop Scheffer, President Vladimir Putin stressed that the level of trust between NATO and Russia needs to be raised.

"However, every country has the right to choose whatever option it considers most effective for ensuring its security." |

|

| RUSSIA and the challenges of the global governance |

| WALK OF SOLIDARITY |

| Russian attack on Ukraine commemorated: 'Support as long as necessary'

Russia's attack on Ukraine is being commemorated in several places around the world. Two years ago this day, the Russians attacked Ukraine |

THE HAGUE |

Alexei Anatolyevich Navalny (4 June 1976 – 16 February 2024) was a Russian opposition leader, lawyer, anti-corruption activist, and political prisoner. He organised anti-government demonstrations and ran for office to advocate reforms against corruption in Russia and against President Vladimir Putin and his government. Navalny was founder of the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK). He was recognised by Amnesty International as a prisoner of conscience, and was awarded the Sakharov Prize for his work on human rights.

In December 2023, Navalny went missing from prison for almost three weeks. He re-emerged in an Arctic Circle corrective colony in the Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug. On 16 February 2024, the Russian prison service reported that Navalny had died at the age of 47. His death sparked protests, both in Russia and in various other countries. Accusations against the Russian authorities in connection with his death have been made by many Western governments and international organisations. On Friday, March 1, he was buried at the Borisov cemetery. |

| International Criminal Courts |

|

The International Court of Justice (ICJ), the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, held public hearings on the preliminary objections raised by the Russian Federation in the case concerning Allegations of Genocide under the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Ukraine v. Russian Federation: 32 States intervening) from Monday 18 to Wednesday 27 September 2023, at the Peace Palace in The Hague, the seat of the Court |

| International Centre for the Prosecution of the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine |

The CCW - A People's Tribunal of the Citizens of the World" has been inaugurated by Ben Ferencz (103 † 7/4/2023). Vladimir Putin on trial in The Hague for crime of aggression against Ukraine. |

| NATO - Russia |

| Since Russia began its aggressive actions against Ukraine, Russian officials have accused NATO of a series of threats and hostile actions. This webpage sets out the facts.

At the NATO Summit in Madrid, Allies agreed that Russia is the most significant and direct threat to their security and to peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area. Russia's brutal war in Ukraine has shattered peace in Europe. Due to its hostile policies and actions, NATO cannot consider Russia to be our partner. NATO does not seek confrontation and poses no threat to Russia. The Alliance will continue to respond to Russian threats and actions in a united and responsible way. |

|

| A geostrategy for Eurasia by Zbigniew Brzezinski (Foreign Affairs, 76:5, September/October 1997)

"Russia must face the fact that Europe and China are already economically more powerful and that Russia is falling behind China on the road to social modernization. In these circumstances, Russia's first priority should be to modernize itself rather than to engage in a futile effort to regain its status as a global power." |

| "Just a territory" to regain a "great empire" (message to Kremlin 28-05-22, 23:46) | Aleksandr Dugin |

Leaders of the Russian Federation brought out evil by violently attacking a sovereign neighboring country. Ukrainians were tortured, raped and killed and dozens of cities destroyed. Why invade if "it's just a territory"?

It is known worldwide there can only be question of a great civilization if it pursues peace and freedom and high artistic styles, ways of thinking in philosophy, and culture. However, apart from a few brief periods of these characteristics (eg. Peter the Great, a Tsar who Loved Science and The Voltaire Library), Russian Federation shows over the course of its history only oppression and conquests of territories. That's actually meaningless or purposeless. Never ever there will be greatness when rulers oppress or when a country grows in size by seizing "just a territory". Only you can make amends again by taking co-responsibility for turning darkness into the light by caring and working for the world. |

August 21, 2022 06:41: the daughter of Russian Aleksandr Dugin, avant-gardist of radicalism and founder of the ideology of neo-Eurasianism, was killed in a suspected car bomb attack near Moscow. |

RF does not want to belong to Europe, nor does it really want to belong to Asia, but still be a territory on the map with its own story.

Russia: conquer Bakhmut (a symbolic 'new East Berlin'). After that the current government to resign and then a government with new leaders accepts an invitation of the UN, which IO takes stock of the demands of both parties and is given the mandate to negotiate demands in order to find a good solution for world peace, and stability in the region. |

|

Aleksandr Gelyevich Dugin is a Russian political philosopher, analyst, and strategist, known for views widely characterized as fascist. He outlined his worldview, calling for Russia to rebuild its influence through alliances and conquest, and to challenge the rival Atlanticist "empire" led by the United States. |

| RUSSIA's POWER |

Russia established worldwide power and influence from the times of the Russian Empire to being the largest and leading constituent of the Soviet Union, the world's first constitutionally socialist state and a recognized superpower, that played a decisive role in the Allied victory in World War II. The Soviet era saw some of the greatest technology achievements of the 20th century, such as the world's first human spaceflight. The Russian Federation was founded following the Belavezha Accords with dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 ('we conclude that the USSR has ceased to exist as a subject of international law and a geopolitical reality'), but is recognized as the continuing legal personality of the Soviet state. Russia has the world's 12th largest economy by nominal GDP or the 7th largest by purchasing power parity, with the 5th largest nominal military budget. It is one of the five recognized nuclear weapons states and possesses the largest stockpile of weapons of mass destruction. |

Russia is a great power and a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, a member of the G8, G20, the Council of Europe, the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, the Eurasian Economic Community, the OSCE, and is the leading member of the Commonwealth of Independent States. Besides, the twenty year strategic Treaty of Good-Neighborliness and Friendly Cooperation between the People's Republic of China and the Russian Federation (FCT) was signed by the leaders of the two international powers on July 16, 2001.

The treaty outlines the broad strokes which are to serve as a basis for peaceful relations, economic cooperation, as well as diplomatic and geopolitical reliance. Controversially, Article 9 of the treaty can be seen as an implicit defense pact, and other articles point at increasing military cooperation, including the sharing of "military know-how", namely, Chinese access to Russian military technology. |

|

The treaty also encompasses a mutual, cooperative approach to environmental technology regulations and energy conservation; and toward international finance and trade. The document affirms Russia's stand on Taiwan as "an inalienable part of China", and highlights the commitment to ensure the "national unity and territorial integrity" in the two countries. |

| Russia's ruthless medieval aggression |

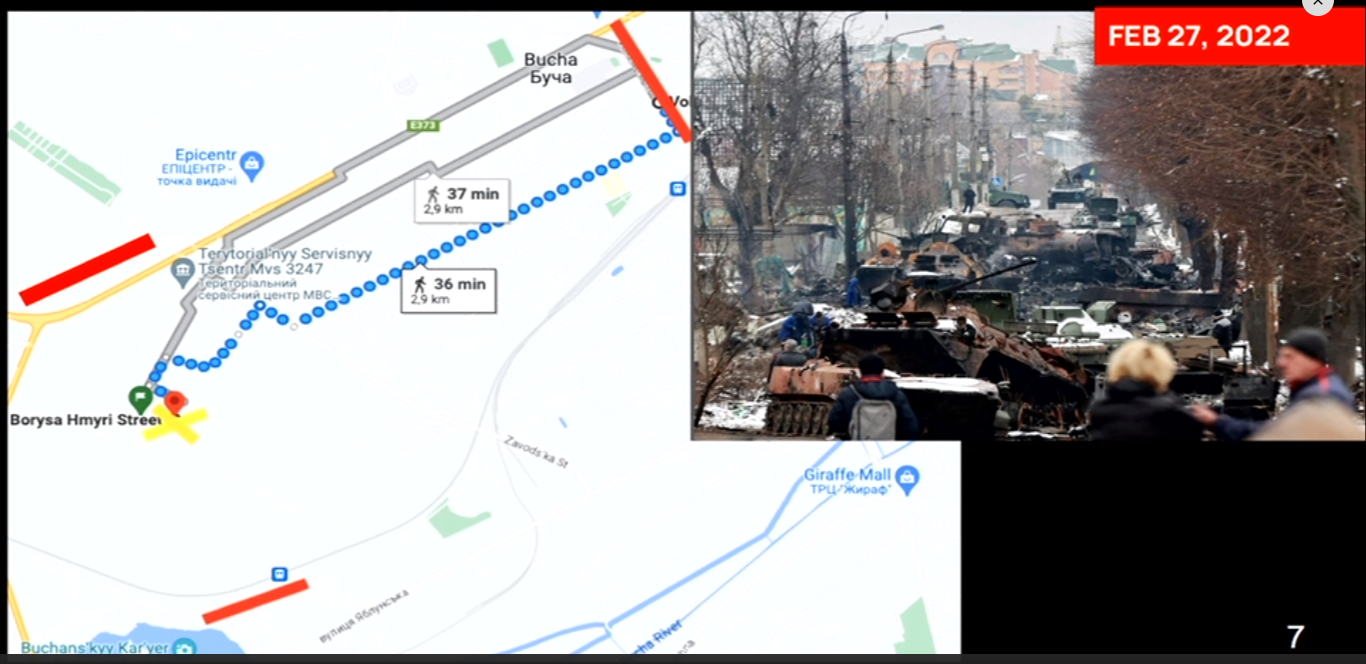

At dawn of 24 February 2022, Russia launched a full-scale invasion against the sovereign country Ukraine. Russian military vehicles crossed the Ukrainian border in several places. |

|

|

|

it seems no exaggeration to say that it is a further continuation of an attack on liberal democracy: |

| Document (with annexes) from the Russian Federation setting out its position regarding the alleged “lack of jurisdiction” of the Court in the case, 7 March 2022.

16 March 2022: World Court orders Russia to halt military operations in Ukraine |

| HOW TO DEAL WITH RUSSIAN FUTURES? |

| RUSSIAN FUTURES 2030: A good policy strategy vis-à-vis Russia is one that does not take the future development of the country for granted but that is well-prepared for a variety of plausible variations of Russian futures. A policy approach that neglects uncertainties and is based on just one likely future – which is most often construed as just the continuation of the present but sometimes (and more dangerously) based on wishful thinking – is a risky one. This kind of conventional policy thinking does not actively prepare for any risks that an unforeseen event or set of developments may entail, and it is likely to also miss the opportunities that could arise as a result of such an unexpected turn of events. Such an approach is particularly detrimental for any actor dealing with Russia, whose leadership is keen to create and exploit surprises that destabilise its adversaries. Thus, linear thinking about Russia and its foreign policy in the 2020s is likely to be a risky policy strategy. A policy that is based on active horizon scanning and anticipation of surprises is likely to be more a flexible and more efficient way of navigating the rough and untested waters of the future. |

The past ten years of EU-Russia relations have been full of surprises and unexpected developments – and the annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine are just two such cases which reverberated across Europe, and forced policymakers to rethink the entire paradigm of how the EU deals with Russia. During this period Europe has been increasingly exposed to Russia’s hybrid interference activities and the EU has struggled to find the right mix of measures to respond. Moreover, although Russia’s strategic goals may remain the same, the tactics it employs to achieve them will almost by definition change. Yet, the Russian leadership may itself be taken by surprise by political transformations within the country. Also, that eventuality does require contingency plans on what is the best way for the EU to position itself in the midst of a more turbulent phase in Russian politics.

This Chaillot Paper (*) has attempted to offer readers some insight into how to structure, test and challenge their thinking about the future of Russia; and by doing so be better prepared for the element of uncertainty. However, this is just the beginning, not the end, of thinking and planning on how to make the most of Russia’s future – whatever that may turn out to be. . |

|

(*) Chaillot Papers are the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS) flagship publication. Written by the Institute’s analysts, as well as external experts and based on collective work or individual research, they deal with all subjects of current relevance to the Union’s security. |

| Ukraine and Russian Federation

Entry into force: 23 April 2004, in accordance with article 6 |

Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 27 March 2014

[without reference to a Main Committee (A/68/L.39 and Add.1)] 68/262. |

| PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY |

| PUTIN’S ASYMMETRIC ASSAULT ON DEMOCRACY IN RUSSIA AND EUROPE: IMPLICATIONS FOR U.S. NATIONAL SECURITY (JANUARY 10, 2018):

Nearly 20 years ago, Vladimir Putin gained and solidified power by exploiting blackmail, fears of terrorism, and war. Since then, he has combined military adventurism and aggression abroad with propaganda and political repression at home, to persuade a domestic audience that he is restoring Russia to greatness and a respected position on the world stage. All the while, he has empowered the state security services and employed them to consolidate his hold on the levers of political, social, and economic power, which he has used to make himself and a circle of loyalists extraordinarily wealthy. Democracies like the United States and those in Europe present three distinct challenges to Mr. Putin. First, the sanctions they have collectively placed on his regime for its illegal occupation of Crimea and invasion of eastern Ukraine threaten the ill-gotten wealth of his loyalists and hamper their extravagant lifestyles. Second, Mr. Putin sees successful democracies, especially those along Russia’s periphery, as threats to his regime because they present an attractive alternative to his corrupt and criminal rule. Third, democracies with transparent governments, the rule of law, a free media, and engaged citizens are naturally more resilient to the spread of corruption beyond Russia’s borders, thereby limiting the opportunities for the further enrichment of Putin and his chosen elite. While the countries of Europe have each had unique responses to the Kremlin’s aggression, they have also begun to use regional institutions to knit together their efforts and develop best practices. NATO and the EU have launched centers focused on strategic communications and cyber defense, and Finland’s government hosts a joint EU/NATO center for countering hybrid threats. A number of independent think tanks and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) have also launched regional disinformation monitoring and fact-checking operations, and European governments are supporting regional programs to strengthen independent journalism and media literacy. Some of these initiatives are relatively new, but several have already begun to bear fruit and warrant continued investment and broader expansion. Through the adoption of the Third Energy Package, which promotes energy diversification and integration, as well as a growing resistance to the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, many European countries are reducing their dependence on Russian energy supplies, though much remains to be done. Despite the clear assaults on our democracy and our allies in Europe, the U.S. government still does not have a coherent, comprehensive, and coordinated approach to the Kremlin’s malign influence operations, either abroad or at home. |

Although the U.S. government has for years had a patchwork of offices and programs supporting independent journalism, cyber security, and the countering of disinformation, the lack of presidential leadership in addressing the threat Putin poses has hampered a strong U.S. response. In early 2017, Congress provided the State Department’s Global Engagement Center the resources and mandate to address Kremlin disinformation campaigns, but operations have been stymied by the Department’s hiring freeze and unnecessarily long delays by its senior leadership in transferring authorized funds to the office. While many mid-level and some senior-level officials throughout the State Department and U.S. government are cognizant of the threat posed by Mr. Putin’s asymmetric arsenal, the U.S. President continues to deny that any such threat exists, creating a leadership vacuum in our own government and among our European partners and allies. KEY RECOMMENDATIONS The recommendations below are based on a review of Mr. Putin’s efforts to undermine democracy in Europe and effective responses to date. By implementing these recommendations, the United States can better defend against and deter the Kremlin’s malign influence operations, and strengthen international norms and values to prevent such behavior by Russia and other states. A more comprehensive list of recommendations can be found in Chapter Eight. 1. Assert Presidential Leadership and Launch a National Response: President Trump has been negligent in acknowledging and responding to the threat to U.S. national security posed by Mr. Putin’s meddling. The President should immediately declare that it is U.S. policy to counter and deter all forms of Russian hybrid threats against the United States and around the world. The President should establish a high-level inter- agency fusion cell, modeled on the National Counterterrorism Center (NCTC), to coordinate all elements of U.S. policy and programming in response to the Russian government’s malign influence operations. 2. Support Democratic Institution Building and Values Abroad and with a Stronger Congressional Voice: Democracies with transparent governments, the rule of law, a free media, and engaged citizens are naturally more resilient to Mr. Putin’s asymmetric arsenal. The U.S. government should provide assistance, in concert with allies in Europe, to build democratic institutions within the European and Eurasian states most vulnerable to Russian government interference. Using the funding authorization outlined in the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act as policy guidance, the U.S. government should increase this spending in Europe and Eurasia to at least $250 million over the next two fiscal years. |

To reinforce these efforts, the U.S. government should demonstrate clear and sustained diplomatic leadership in support of individual human rights that form the backbone of democratic systems. Members in the U.S. Congress have a responsibility to show U.S. leadership on values by making democracy and human rights a central part of their agendas. They should conduct committee hearings and use other platforms and opportunities to publicly advance these issues.

3. Expose and Freeze Kremlin-Linked Dirty Money: Corruption provides the motivation and the means for many of the Kremlin’s malign influence operations. The U.S. Treasury Department should make public any intelligence related to Mr. Putin’s personal corruption and wealth stored abroad, and take steps with our European allies to cut off Mr. Putin and his inner circle from the international financial system. The U.S government should also expose corrupt and criminal activities associated with Russia’s state-owned energy sector. Furthermore, it should robustly implement the Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act and the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which allow for sanctions against corrupt actors in Russia and abroad. In addition, the U.S. government should issue yearly reports that assign tiered classifications based on objective third-party corruption indicators, as well as governmental efforts to combat corruption. 4. Subject State Hybrid Threat Actors to an Escalatory Sanctions Regime: The Kremlin and other regimes hostile to democracy must know that there will be consequences for their actions. The U.S. government should designate countries that employ malign influence operations to assault democracies as State Hybrid Threat Actors. Countries that are designated as such would fall under a preemptive and escalatory sanctions regime that would be applied whenever the state uses asymmetric weapons like cyberattacks to interfere with a democratic election or disrupt a country’s critical infrastructure. The U.S. government should work with the EU to ensure that these sanctions are coordinated and effective. 5. Publicize the Kremlin’s Global Malign Influence Efforts: Exposing and publicizing the nature of the threat of Russian malign influence activities, as the U.S. intelligence community did in January 2017, can be an action-forcing event that not only boosts public awareness, but also drives effective responses from the private sector, especially social media platforms, as well as civil society and independent media, who can use the information to pursue their own investigations. The U.S. government should produce yearly public reports that detail the Russian government’s malign influence operations in the United States and around the world. 6. Build an International Coalition to Counter Hybrid Threats: The United States is stronger and more effective when we work with our partners and allies abroad. The U.S. government should lead an international effort of like-minded democracies to build awareness of and resilience to the Kremlin’s malign influence operations. Specifically, the President should convene an annual global summit on hybrid threats, modeled on the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL or the Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) summits that have taken place since 2015. Civil society and the private sector should participate in the summits and follow-on activities. |

Specifically, the President should convene an annual global summit on hybrid threats, modeled on the Global Coalition to Counter ISIL or the Countering Violent Extremism (CVE) summits that have taken place since 2015. Civil society and the private sector should participate in the summits and follow-on activities.

7. Uncover Foreign Funding that Erodes Democracy: Foreign illicit money corrupts the political, social, and economic systems of democracies. The United States and European countries must make it more difficult for foreign actors to use financial resources to interfere in democratic systems, specifically by passing legislation to require full disclosure of shell company owners and improve transparency for funding of political parties, campaigns, and advocacy groups. 8. Build Global Cyber Defenses and Norms: The United States and our European allies remain woefully vulnerable to cyberattacks, which are a preferred asymmetric weapon of state hybrid threat actors. The U.S. government and NATO should lead a coalition of countries committed to mutual defense against cyberattacks, to include the establishment of rapid reaction teams to defend allies under attack. The U.S. government should also call a special meeting of the NATO heads of state to review the extent of Russian government- sponsored cyberattacks among member states and develop formal guidelines on how the Alliance will consider such attacks in the context of NATO’s Article 5 collective defense provision. Furthermore, the U.S. government should lead an effort to establish an international treaty on the use of cyber tools in peace time, modeled on international arms control treaties. 9. Hold Social Media Companies Accountable: Social media platforms are a key conduit of disinformation campaigns that undermine democracies. U.S. and European governments should mandate that social media companies make public the sources of funding for political advertisements, along the same lines as TV channels and print media. Social media companies should conduct comprehensive audits on how their platforms may have been used by Kremlin-linked entities to influence elections occurring over the past several years, and should establish civil society advisory councils to provide input and warnings about emerging disinformation trends and government suppression. In addition, they should work with philanthropies, governments, and civil society to promote media literacy and reduce the presence of disinformation on their platforms. 10. Reduce European Dependence on Russian Energy Sources: Payments to state-owned Russian energy companies fund the Kremlin’s military aggression abroad, as well as overt and covert activities that undermine democratic institutions and social cohesion in Europe and the United States. The U.S. government should use its trade and development agencies to support strategically important energy diversification and integration projects in Europe. In addition, the U.S. government should continue to oppose the construction of Nord Stream 2, a project which significantly undermines the long-term energy security of Europe and the economic prospects of Ukraine. |

|

|

|

| Valdai Club |

At the round table at the Valdai Club on Monday, Carl Bildt hailed participants of the Euromaidan as the first truly post-Soviet generation in Ukraine. But a generational shift has taken place in Russia, too. Those who were born after 1991 experienced an era of relative prosperity and national pride in their teens and witnessed the post-Crimean euphoria in 2014. They did not inherit the feeling of national weakness that came with the experience of the USSR collapse, which became formative for many of those Russians who are now in their thirties and forties. Do you feel this fact is overlooked in the West? |

|

I believe the generational dimension is very important and should be taken very seriously – all over Europe. In Russia, you have a younger generation, which is certainly the most westernized – at the level of their consumption or travel habits and so on – but at the same time the most anti-western one.

This is not a new phenomenon. This can often be seen in many countries of the world. The post-Cold war period was an age of imitating the West and the result of this imitation is both growing similarity and resentment. In terms of their attitude to the West, this generation resembles any second generation of immigrants, who are better integrated and at the same time much more resentful. This generation’s idea is that they want to be proud of their country. Many of them want to get the recognition of the West by opposing the values and norms of this same West. This is not unique for Russia. Look at other post-communist countries. At the recent elections In Poland, 60 percent of people younger than 29 voted for parties which make national dignity their major story. This is largely the result of disappointment in cosmopolitanism and globalization promoted after the collapse of the Eastern Bloc. So, some things we think are exceptional for Russia or Ukraine are part of bigger European trends. What we see all over Europe is the rise of identity politics. People in the West tend to compare Ukraine to Poland in 1989, but what is happening there rather resembles the painful process of nation-building that we witnessed at the time of disintegration of colonial empires in the 1960s and 1970s. Russia is also in the process of state-building because historically, Russia never had an empire, it was one. So, unlike England, it could not simply cut itself off from its overseas possessions. In order to understand what is happening in Ukraine, we should rather look at the experience of countries like Algeria in the 1960s than Poland in the 1980s. That’s why you have the rise of anti-Russian sentiments there – this is the type of things that states are built with. If you look at how the ongoing confrontation with Russia is reflected in the Ukrainian social media, you can notice that the most rabid anti-Russian comments are often left in the Russian language and by people with Russian names. Interestingly, it is as common to see Russians with Ukrainian names promoting Russia’s cause in online battles, given the significant proportion of ethnic Ukrainians in Russia’s population. This is the most important argument for my case. Being Ukrainian today does not depend on the language you speak. The war in Ukraine paradoxically liberated Russian language. Today, Ukrainian identity is defined by the position you take in the war in Ukraine and not by the language you speak. |

In comparing the identity-building processes in the post-Soviet space I was always fascinated by the case of Belarus. They do not have a strong nationalistic tradition to go back to, like, for example, western Ukraine. So, Lukashenko succeeded in taking the Soviet legacy to the core of their identity. In fact, Belarusians began to build the identity of the last Soviets, while everybody was against that. For him, it was an identity that had to be distinctive from what was happening in Russia. So he did not go anti-Russian in building the identity of Belarusians, opposing to the anti-Soviet discourse of Russians instead.

I’m saying this because many are surprised by the rise of anti-Russian sentiments in Ukraine, neglecting the fact that states are traditionally built not only by borders and constitutions but also by certain mobilization of national sentiments.

The rise of nationalism was easy to predict. If you take the post-Yugoslav space, you realize what kind of states can emerge out of post-Communist disintegration and what kind of stuff national identities are made of. And this is a huge problem for the European political and intellectual elites. In the words of historian Charles Tilly, “states make wars, but wars make states”. The traditional framework of the EU-Russia relations has been impacted by new factors – the refugee crisis in Europe and the decline in energy prices. Do you feel these crises offer Russia and the EU an opportunity to rethink their relations and to start from scratch? At present, society is consolidated around President Putin but it is difficult to imagine how post-Putin Russia will look like. As a result, the domestic political crises (which are very important because they are essentially about identity and survival of these states) and the way we will react to them will largely define the relations between Russia and the European Union. Here, we have two scenarios: We can try to cope with this crisis by better regulating our relationship, trying to guarantee that the policies of the other are not an additional destabilizing factor. Or we can use the confrontation with each other for domestic political consolidation. I believe the choice is to be made. This will shape the relations between Russia and the European Union and from this point of view 2016 is going to be more important than the previous two years. |

| RUSSIA_EU |

| RUSSIA, EU SHOULD HAVE CLEAR LONG-TERM OBJECTIVES IN BUILDING RELATIONSHIP (Lavrov in Voice of Russia, Interfax, 13 February 2014) Relations between Russia and the European Union should set clear long-term objectives, and the EU should stop using the friend-or-foe principle in dealing with Russia, says Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov. "It's getting increasingly more obvious that we are being hampered by a lack of clear long-term objectives in resolving specific problems related to the developments on our continent," Lavrov said in an article published in the Thursday issue of Kommersant. "There is the impression that our Western partners often act instinctively, being guided by the simplistic friend-or-foe principle and not thinking too much about far-reaching implications of their steps. Anyway, I think the primitive tug of war between the European Union and Russia cannot meet the realities of international relations, which are getting increasingly more complicated, and is not worthy of the huge political-diplomatic experience the European powers have accumulated for centuries," Lavrov said."The relationship between Russia and the European Union has approached a kind of moment of truth. In order to build cooperation consistently and purposefully, we should understand whether we are determined earnestly to follow the way of achieving ambitious goals of true strategic partnership. Otherwise, we will continue stumbling now and then on the absence of clear objectives. Information wars won't help here. This calls for true leadership and political wisdom," he added."The reflections on what actually prompts our Western partners to be so stubborn in taking the either-or approach in the Ukrainian situation and, rejecting proprieties, bluntly pursue the line of its inclusion in its geopolitical environment inevitably lead to fundamental aspects of relations between the European Union and Russia. It turns out that the present misunderstanding is based on a lack of clarity regarding long-term objectives in the development of relations between Russia and the EU, or, using Javier Solana's expression, a deficit of strategic trust," Lavrov wrote. Western media outlets often resort to anti-Russian information campaigns using Cold War-style phraseology, he said."I had the chance to hear echoes of such judgments at the OSCE ministerial meeting in December 2013 and at the recent jubilee session of the Munich Security Conference. Certainly, society is a living organism, and ideas about values may change as long as it develops. A lot of approaches common in the European Union today were perceived as unacceptable in the same countries just about 20-30 years ago. I mean, in particular, moral relativism, the propagation of permissiveness and hedonism, the strengthening positions of militant atheism, and the rejection of traditional values that have been the moral foundation of human development for centuries. Moreover, these attitudes are being promoted with messianic persistence both in those countries themselves and in their relations with neighbors," he said. Lavrov pointed out in connection with this that "principles of democracy imply above all respect for opinions of others. Everyone should acknowledge that, by agreeing on basic values, including respect for democratic foundations in public affairs, human rights and fundamental freedoms, the peoples of Europe should at the same time allow each other to remain different and retain their cultural identity, in full compliance with universal human rights conventions and declarations," Lavrov said. |

|

|

| Aggression against Baltic States |

In 1940, in accordance with the secret protocol of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact with Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union directed the occupation and subsequent annexation of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. In each country, demands were made under threat of force from Moscow for puppet communist governments to be formed. Fraudulent elections were held in July 1940 with solely communists being represented in the parliament of each country's government. Those governments then were instructed by Moscow to petition the Soviet government to be added as constituent Soviet republics.

The United States, like other Western democratic powers, such as the United Kingdom, Norway, France, and Denmark, never recognized the incorporation as valid and continued to accredit the legations of Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. On June 23, 1940, U.S. Secretary of State Sumner Welles declared the American non-recognition policy on the principles of the Stimson Doctrine. The policy was maintained until the 1991 restoration of independence in all three countries. |

Report of the Select Committee to investigate communist aggression and the forced incorporation of the Baltic States into USSR (third interim report, 1954) |

| ARTS and CULTURE |

|

|

|

|

The National Library of Russia (the NLR), one of the largest libraries on the world, was based in the Imperial Public Library in St. Petersburg. The Library was established in 1795 by Catherine the Great. The NLR consists of 36 million books as well as Voltaire’s Library, where a unique collection of his works of the Age of the Enlightenment resides. Voltaire’s Library consists of 6814 volumes, almost one third of them is marked by the former owner, Voltaire. Catherine the Great ordered those rare books from the private Voltaire’s library, all the volumes were delivered from Ferney to St. Petersburg in 1779. Explore the history of the Library along with its collection of historical works, science, art and philosophical dissertations including works of Voltaire, Diderot and Rousseau. Another story is The philosophers' ships or philosopher's steamboats, steamships that transported intellectuals expelled from Soviet Russia in 1922 with, among others, one of Putin’s Rasputins Ivan Ilyin. The main load was handled by two German ships, the Oberbürgermeister Haken and the Preussen, which transported more than 200 expelled Russian intellectuals and their families in September and November 1922 from Petrograd (modern-day Saint Petersburg) to the seaport of Stettin in Germany (modern-day Szczecin in Poland). Three detention lists included 228 people, 32 of them students. Later in 1922, other intellectuals were transported by train to Riga in Latvia or by ship from Odessa to Istanbul.

St. Petersburg International Cultural Forum - a unique place, where every year specialists from the sphere of culture, politics, public authorities and businesses meet each other |

| IMMIGRATION |

| Immigrant Russia - a crisis of demography or ethnicity? (by Ben Judah - 26 Oct 10)

Hamid drives a clapped-out Soviet bus in a Russian mining colony beyond the Arctic Circle, where temperatures regularly plunge below minus forty. Yet this native of the Uzbek deserts has few regrets about his decision to migrate to Putin’s empire. “In my country there more men than jobs - In Russia there are more jobs than men.” He expresses himself in the faultless Russian of a Soviet education. “It’s easy for us to come and work here. The borders are not hard to cross, we speak the language and there are lots of people who can make you the permits.”Russia is now an immigrant society. In Moscow and other major cities, migrants from the ex-Soviet states of Central Asia, the Caucasus and Eastern Europe do the work that natives turn down. Tajiks sweep the streets, Moldovans wait tables and Uzbeks work on construction sites. The metro flutters with flyers stuck inside carriages hawking the mobile numbers of professional forgers -“We Make Your Moscow Permit.”Russia has become the second most popular destination for migrants in the world after the USA. In St. Petersburg hour long queues snake round the migration bureau where hundreds of migrants nervously swap cigarettes for job tips as they wait to register. Magadan on the Pacific has several Georgian restaurants and even on the dirt tracks of northern Siberia, Uzbek cafeterias are not uncommon.Visa-free regimes between Russia and most of her former colonies, along with the endemic corruption of her Gogolian officialdom, mean few bother with the hassle of formal immigration. Nor have many much intention of returning to their weak and mostly impoverished states for more than a holiday. In 2009 the Russian Migration Service claims over 10 million migrants entered the country. They add that as many as 5 million illegals“are living in the shadows.” Many experts agree that the migrant population is over 8.5 million, although off the record, some diplomats suggest the real figure may be over 15 million. That would be roughly 8 million more workers that the 6.7 million drop that Russia has recorded since 1991. |

| Ethnic or demographic crisis?

The danger of demographic collapse is frequently cited as the Achilles heel of Russia, with the original BRIC report noting that it posed a danger to the country’s growth. In fact Russia does not have an economic demographic crisis – instead she has a demographic crisis in terms of ethnic Russians and fully fledged citizens as a proportion of the population.Ethnic Russians were officially 79% of the population in the suspect 2002 census which did not include migrants, and was widely accused of exaggerating the number of Russians while masking Chechen demography. Taken at face value the census suggests the country is as Russian as Israel is ethnically Jewish or the United States racially ‘white.’ However, if you include migrant workers, ethnic Russians may make up as little as 73% of those living in Russia. This multi-ethnic composition echoes back to imperial past of both Tsarist Russia and the USSR. Slavic Soviet elites voiced concerns throughout the 1970s and 80s about what they called “the yellowing” of their country, and the fact that ethnic Russians made up just 50% of the population by 1990 played a part in President Yeltsin precipitating the break-up of the USSR. |

The news that Russia’s notoriously low birth-rates have picked up in recent years is of some comfort to the Kremlin. Levels today are comparable to other European countries, and higher than some – for instance Italy or Hungary. This contrasts with 1999 when post-Soviet fertility rates hit rock bottom at just 1.16, at a time when 40% of Russia’s population earned less than the official poverty rate. By 2009, when the numbers in official poverty dropped to around 10%, the fertility rate rose to 1.54. The Health Ministry says that in September 2009 births outnumbered deaths for the first time since 1994.

It is Russia’s male death rates – not birth-rates – that mark her out from the rest of the developed world. Male life expectancy is only 59 – compared to 73 for Palestinian men. However, male life expectancy did rise by four years between 2005 and 2009.This slight improvement is partly due to the steady emergence of a private healthcare industry with access to western drugs. Russians were poorly nourished in the shortage economy of the late 1980s and early 1990s when adverse demographic trends set in. Now supermarkets and the availability of imported food are playing their part in these incremental improvements.Russia’s demographics are still bad, but the country is not ‘dying out’ just yet thanks to these positive signs that the population is at least starting to recover. And, as well as a likely reliance on migrants for decades to come, it is striking that the highest birth rates in the Federation are in the non-ethnic Russian republics of the North Caucasus and outer Siberia. The Russian military is concerned that by 2015 an estimated third of its conscripts may be of Muslim origin, many from the war-torn Caucasian regions they are expected to serve in. The decline in the Russia population in both the Far East and republics such as Chechnya, Ingushetia and Dagestan will make it far harder for the Kremlin to dictate their future.Will mass-migration modernise Russia?What insider Gleb Pavlovsky has called “a sociologically obsessed Kremlin” is trying to discreetly fashion a more multi-cultural society. In April, Putin himself bluntly declared that “the door will always be open” for those that wanted to tie their future to Russia. In September the head of the Federal Migration Service said migrants were the key to improving the country’s demographic situation. This echoed another statement by Putin in April that Russia was aiming to make foreign workers “feel more at home in Russia”, as he further liberalised labour laws with Kazakhstan and Belarus.Last year the Kremlin claimed that the number of Russian citizens increased for the first time in 15 years – albeit it by a rather measly 25,000 – thanks to 330,000 new citizenships being awarded (mostly to migrants).But benefiting from migration involves more than just letting people in. Most migrants live in penury and often suffer harassment by skinheads. Transient and largely unprotected by labour laws, their presence in turn risks driving down the wages of other workers and prolonging the lives of otherwise defunct and uncompetitive Soviet factories.Mass migration has also politicised elements of Russia’s working class. The ‘Movement Against Illegal Immigration’, the myriad skin-head gangs and neo-Nazi brotherhoods have mobilised the energies of the losers of Putinism – a de-industrialised underclass who desperately need economic modernisation, an enabling welfare state and a crackdown on corruption. Ethnic struggles have eclipsed class struggle on the streets.Migrants may yet save the Russian economy from a demographic crunch. Yet if Putin’s plans do not include strengthening the rule of law, they could lead to other challenges to the Russian state, holding back the modernisation of the country’s creaking industry and emptying what it means to be a ‘Russian citizen.’ (source: ECFR) |