In a hotel ballroom in Rome, leaders of the nationalist right took a grim view of Western liberal democracy—which Cold War conservatives deeply believed in. February 10, 2020 Anne Applebaum Staff writer at The Atlantic:

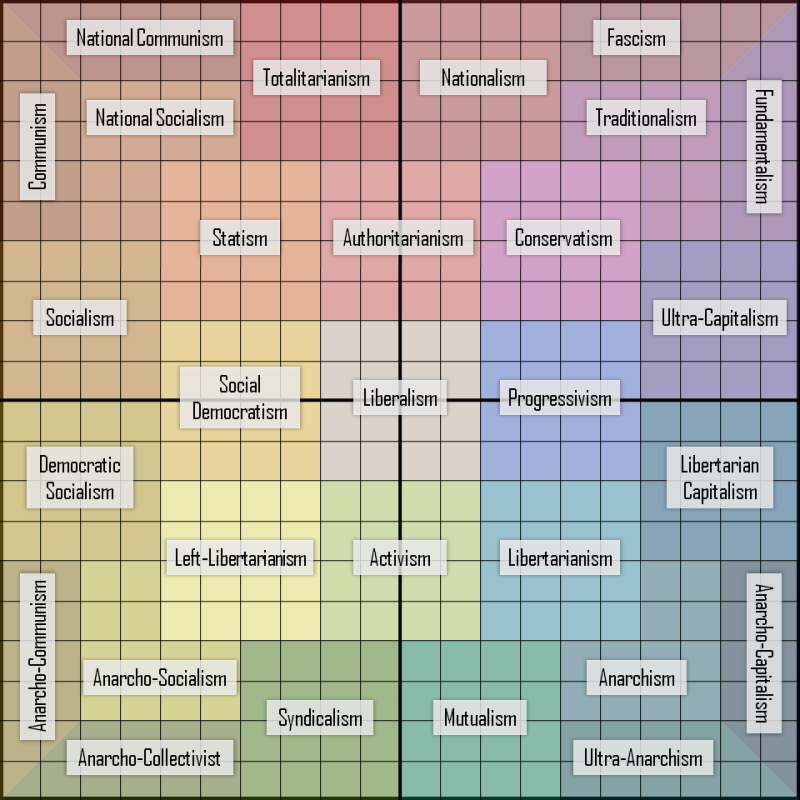

In an Italian hotel ballroom of spectacular opulence—on red velvet chairs, beneath glittering crystal chandeliers and a stained-glass ceiling—the conservative movement that once inspired people across Europe, built bridges across the Iron Curtain and helped to win the Cold War came, finally, to an end.The occasion was a conference in Rome last week called “God, Honor, Country: President Ronald Reagan, Pope John Paul II, and the Freedom of Nations.” Inspired by the Israeli writer Yoram Hazony, convened under the banner of “National Conservatism,” this event was co-organized by Chris DeMuth, a former president of the American Enterprise Institute (in the era when it supported global capitalism and the Iraq War) and John O’Sullivan, a former speechwriter for British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. O’Sullivan now runs the Danube Institute, which is funded, via a foundation, by the Hungarian government. The conference itself was funded, according to DeMuth, by an anonymous American donor. This was the successor to the National Conservatism Conference held in Washington, D.C., last year. That occasion featured a strange agglomeration of new and old conservatives, including both John Bolton and Tucker Carlson, people who still talk hopefully about shrinking the state and those who want to enlarge it, people still jockeying to be relevant and people full of confidence that they now are.The conference in Rome was different in many ways, beginning with the aesthetics: No room in Washington contains quite so many Corinthian columns. The purpose, at least at first, seemed a little more mysterious, too. If Reagan and John Paul II were linked by anything, it was a grand, ambitious, and generous idea of Western political civilization, one in which a democratic Europe would be integrated by multiple economic, political, and cultural links, and held together beneath an umbrella of American hegemony. John Paul II wanted Poland to join the European Union; in his famous speech in Normandy, Reagan declared that not just “one’s country is worth dying for,” but “democracy is worth dying for, because it’s the most deeply honorable form of government ever devised by man.” At least when she was still prime minister, Margaret Thatcher was also a proponent of this vision of the West. She was one of the driving forces behind the European single market, the continent-wide free-trade zone that also required a unified regulatory system—the same unified regulatory system that the British have now rejected—and had great faith in the importance of human rights. She said so explicitly: “The state is not, after all, merely a tribe. It is a legal entity,” Thatcher declared in Zagreb, Croatia, in 1998, according to her biographer Charles Moore. “Concern for human rights … thus complements the sense of nationhood so as to ensure a nation state that is both strong and democratic.”The new national conservatism, at least as articulated in Rome, is very different from Reaganism and Thatcherism. The starting point is that European integration and American hegemony are both evil, and that universal ideals like human rights are a dangerous ideology. These, in fact, are arguments made in Hazony’s book, The Virtue of Nationalism, a work that synthesizes biblical history, the writings of John Locke, and contemporary politics into a caricature of a political philosophy for our times. Hazony has invented a definition of the nation—tribes that have agreed to live together, more or less—that applies to no existing modern state, not even Israel.

He also attributes all of the good things about modern civilization to the nation and all of the bad things to what he calls “imperialism.” He puts countries and institutions he likes into the first box, and those he doesn’t like into the second. Thus it emerges that the Nazis, who specifically called themselves nationalists, were not nationalists but imperialists, as is the European Union, an organization created to prevent the resurgence of Nazism. Britain, Spain, and France, despite their long history as empires on land and sea, count as nations. |

|

In this worldview, democracy is of no significance. International treaties and obligations do not matter either, not even if people want them. Although membership in the European Union is voluntary—Brexit has just proved that—and is supported by majorities in most countries, Hazony writes and speaks as if the EU were an occupying power.

Just because his thesis is ahistorical and internally contradictory does not mean that it cannot be influential. Many bad books have had great influence. This one has been very lucky, having appeared just as the word nationalism was adopted by Donald Trump, who finds it a useful way of dressing up a set of foreign and domestic policies that are largely governed by his whims and dictated by his self-interest. Mike Pompeo, the secretary of state, has used the language of nationalism as well. Hazony’s book also appeared at the moment when a handful of Anglo-American conservative intellectuals, jolted out of their old alliances by Trump and Brexit, were looking for a new project—and just when the parties of the European far right were craving the legitimacy that can be granted by British, American, and especially Israeli friends. To put it differently: The arc of history once described by Martin Luther King and Barack Obama is now bending the other way, and a lot of people are leaping aboard. The sight of an intellectual elite undergoing a radical shift in its views and alliances is never elegant, and this event had some rough edges. Hazony’s opening speech set a strange tone. He once again set up black-and-white categories, contrasting (bad) “enlightenment rational liberals” who have no ties to family or place with (good) conservatives who do, thus leaving out a very large, and much more nuanced, third category: the many enlightenment rational liberals who are patriotic, take care of their children, and feel attached to their local customs. He attacked the euro, Europe’s common currency, not for its economic faults but because euro notes are decorated with drawings of imaginary bridges instead of drawings of real ones. He declared that European children “are not taught that there is such a thing as a nation.” Of course he has every right to evoke an old and legitimate political tradition—Burkean conservatism has been with us for a long time—but some of this was silly. At different times my children went to Polish, British, and American schools, and they learned about “the nation” in all of them. It’s also ridiculous to claim that liberal Europeans never speak of their nations with pride. On the very day Hazony was lecturing in the hotel ballroom in Rome, the president of France was lecturing at a university in Krakow, declaring that he feels “proud to be French and proud to be European,” and saying he expects that Poles feel the same way too. To millions of people, these things do not feel contradictory. But other speakers in Rome also reflected an almost paranoid sense of persecution. The idea that “the nation” has been outlawed is clearly something that a certain breed of conservative now genuinely perceives to be true. The American Christian writer Rod Dreher solemnly described a world in which he felt repressed, just as people had been under totalitarian communism. “The all-consuming ideology among us is … a globalist, victim-focused identity politics, often called ‘social justice,’” he warned, calling on audience members to think of themselves as Christians persecuted for their faith in the past. Roberto de Mattei, an Italian Catholic intellectual, spoke darkly of a “dictatorship of relativism” and declared that the progressive establishment had banned the writing of books about the history of communism. Since I have personally written three books about the history of communism, all of which have been published in multiple European languages—including Italian—I found this statement mystifying.

What makes this view odder is that it also clashes with political reality. National conservatives cannot simultaneously be helpless victims of a totalitarian culture and also hold enormous political power, which some of them plainly do. Not all of these powerful new nationalists made the conference. Trump, obviously, was otherwise occupied. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was not there either. Matteo Salvini—the nationalist far-right leader who is Italy’s former deputy prime minister and maybe the next prime minister—was supposed to be there but dropped out at the last minute, possibly because he thinks that more votes can now be had by associating with enlightenment rational liberals. |

|

| British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government is, at least for the moment, also tacking to the center. The only elected British politician I spotted at the Rome conference was an eccentric Tory MP named Daniel Kawczynski, who is best known as a vocal supporter of the Russian president, Vladimir Putin.

Nevertheless, given that neither O’Sullivan nor DeMuth is any longer at the center of British or American political debate—O’Sullivan now lives in Budapest and runs an institute funded by the Hungarian government—and given that Hazony is a marginal figure in Israel, the number of European politicians with very real political ambitions and genuine influence who did appear is striking. The divisive and eloquent Thierry Baudet, the Dutch nationalist far-right leader—his party commands about 15 percent of the vote in the Netherlands, a lot in that country’s fragmented system—was on a panel. A politician from Vox, the rapidly growing Spanish party that has broken the post-Franco taboo on nationalist politics, was present too. Marion Marechal, the French politician who has dropped the surname Le Pen but still belongs to the family that founded the French party now known as the National Rally, spoke at length. Marechal, who is sometimes described as a candidate for the French presidency in 2022, made a well-crafted speech that, like Hazony’s, drew a sharp, polarizing contrast between conservatives and enlightenment rational liberals, whom she called “progressives.” The term seemed to include everybody from President Emanuel Macron to French Stalinists. Her words were evocative: “We are trying to connect the past to the future, the nation to the world, the family to the society … We represent realism; they are ideology. We believe in memory; they are amnesia.” But her remarks don’t reflect reality. Macron spoke explicitly and at length about history and memory in Krakow, and has done so on many other occasions too. To Marechal’s fans, that may not matter. Perhaps they feel themselves to be a persecuted minority, and she echoes that view. Perhaps they just prefer to hear about history from someone like her, the spokesman for an ethnic definition of France and Frenchness, instead of Macron.Still, if it is true that the new nationalists caricatured liberals, then it is equally true that liberals often caricature the new nationalists, and I don’t want to do so. Some of what Marechal says to the French, and some of what Baudet says to the Dutch, is indisputably true. Economies really have become more global, which makes small communities more vulnerable; older landscapes have been destroyed by modernity; people have drifted away from churches, probably for good; technology is moving very quickly, in ways that frighten people. The argument is over how to address the legitimate fears created by these changes. Among others, the European Union itself has come up with a set of solutions, including the donation of money to culture and architecture and the protection of European agriculture, and thus European landscapes, against competition. You can argue about whether these things work, but in a world dominated by an erratic America and an authoritarian China, the EU remains the only entity large enough to speak up for Europe on the world stage. The Netherlands alone—even Britain alone—will not be able to do it. But other possibilities exist too. One can use the electorate’s fears, for example—fan them, exploit them—in order to build a new political movement. And because national conservatism very much wants to be a new political movement, this is a prospect that interests many people. Thanks to some rather less eloquent speeches on Polish patriotism and the glories of “sovereignty,” the audience in Rome thinned out significantly as the day wore on.

But as the final session grew closer, cameramen and journalists began drifting back into the room. When the final speaker entered, he won a standing ovation. This was Viktor Orbán, the Hungarian prime minister, the man whose career probably best illustrates the distance that the conservatism of Reagan and Thatcher has traveled since 1989. Orbán, I realized, was the person that many in the room had really come to hear. |

|

Famously, Orbán has gone one step further than many other European conservatives. For one, he has not been shy about using conspiratorial, sometimes hysterical nationalist language, echoing old anti-Semitic tropes, in order to exploit fear of the outside world. “We are fighting an enemy that is different from us,” he said in 2018. “Not open, but hiding; not straightforward but crafty; not honest but base; not national but international; does not believe in working but speculates with money; does not have its own homeland but feels it owns the whole world.” More important, he has surpassed everyone else in Europe in his willingness to destroy the institutions that create the terrain that make democracy possible. Although conference participants in Rome spoke at length about oppressive left-wing ideology at universities, Hungary is the only European country to have shut down an entire university, to have put academic bodies (the Hungarian Academy of Sciences) under direct government control, and to have removed funding from university departments that the ruling party dislikes for political reasons. Although many said they feel repressed by left-wing media, Hungary is also the only European country that has used a combination of political and financial pressure to put most of the private and public media under ruling-party control too.

Orbán’s destruction of independent press and academia and his slow politicization of the Hungarian courts have served a purpose quite different from lofty ideas about national sovereignty or the beauty of landscapes. These machinations have enabled the prime minister’s family and his inner circle to camouflage the myriad ways in which they use state power to get rich. They have also helped him fiddle with electoral rules, gerrymander districts, and adjust the constitution in order to make sure he doesn’t lose. He usually pushes right up to the edge of authoritarianism without going over it—almost always avoiding violence, for example—not least because Hungary gets a lot of money from the EU, some of which personally benefits his party colleagues. But if, eventually, the EU disappears, he will no longer need that restraint. His country is the best illustration of what happens when you dismiss universal values, repress journalists and academics who produce facts, undermine courts and the rule of law: When you get rid of all of those things, you are just a few short steps away from corruption and tyranny. This is the real face of the new “nationalism,” however carefully it is hidden behind an intellectual facade or dressed up as the successor of Reagan and John Paul II. You can see why it appeals to men like Netanyahu or Trump. Nothing about this approach is a secret, though Orban was not asked about any of it when he appeared onstage. Instead, DeMuth asked him to explain the secrets of his success. With a straight face, Orbán said, among other things, that it helps to have the support of the media. In the back of the room where the press were sitting, a few people laughed. At another point, Orbán also described his political philosophy as “Christian Democracy,” implying that this is something brand-new and radical. In fact it is very old: German, Dutch, and Belgian Christian Democrats were the founders of the European Union, and Angela Merkel, a Christian Democrat and the daughter of a Protestant minister, runs Germany today. She is Christian, but not in the way Orbán or many of the Rome panelists define themselves as Christian. Her Christianity offers moral guidance, not a way to divide “us” from “them.” The latter is an aggressive new political identity that many people in the room seek, especially if it will grant them the right to abolish the rule of law when they gain power.

The world inhabited by Reagan and John Paul II is long past, and no one knows how they would react to so-called cancel culture and Twitter mobs, or the backlash against Western culture on American (but not Hungarian) college campuses, or some of the uglier strains of far-left thinking. But somehow I doubt their response would be the creation of a new, kleptocratic authoritarian right that chips away at the institutions preserving democracy. Nor do I believe they would have wanted to destroy the institutions that have long undergirded the West, as so many of these new “nationalists” want to do. Like Mrs. Thatcher, I aspire to live in “a nation state that is both strong and democratic,” a nation that inspires patriotism and respects the idea of human rights. I don’t see why love of country and love of history would be incompatible with membership in broader Western communities. But in the political world we are now entering, they may soon become so. |

|